Once again, we try to answer one of life’s greatest questions: Can we have everything we want? And, as if that’s not a large enough feat, can we get it all in one neat package, please? Oh, and while we’re being picky, make sure it’s Italian, too.

Thanks, Jeeves. As Russell Baker once opined, “people seem to enjoy things more when they know a lot of other people have been left out of the pleasure.” And so it goes with sport-touring bikes. A good one can do everything well, crossing state lines with ease or annoying your buddy on his race replica, up and down your favorite roads.

He’ll just look at you, then the bike, and scratch his head wondering how any one bike can do both things so competently. As is usually the case with all-’rounders though, good things become okay things, making room for bad things to also become okay things.

What frequently ends up happening is that a manufacturer tries to sell a bike that doesn’t handle like a sport bike, and won’t travel like a touring bike. It’s heavier, slower, wider, uglier and just plain not as much fun as the bikes it draws from. But, hey, you could do a little bit of everything on them if you really worked at it.

In the great sport-touring pantheon of bikes that are supposed to do all things reasonably well, it’s no surprise that so few bikes manage this task in anything that vaguely resembles a competent manner. But either one of the two Italian bikes we have here are as close to hitting the bulls-eye as anything ever produced.

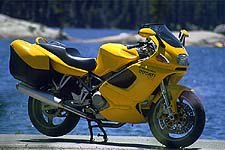

When Ducati introduced it’s ST2 sport-tourer to the world back in 1998, it replaced the company’s rapidly aging Paso as the do-it-all bike in their range. Then, only a year later, the Italian marque released the ST4 which upped the displacement and power output of their new sport-tourer. Other than a larger rear tire and some other small differences, the ST4 and ST2 would be sold along side of each other, separated by a $2,000 price gap and about 22 horsepower.

“The larger of the two Ducati sport-tourers eclipsed the other twin-cylinder machines it was to compete against, and has pretty much held onto this superiority for the past few years.”

Some time last year, however, Aprilia sent us a drawing of its newly proposed sport-tourer. There was also some information that leaked out, hinting at the bike’s supposed superiority over anything ever built for the sport-touring market. And though it would be many months before we got our first glimpse of the new RST Futura, as it was to be called, we knew Ducati would have a serious battle on its hands when this bike arrived on our shores. After spending a good amount of time on the Ducati last year, we grew rather fond of the bike. It seemed to have everything a proper sport-tourer needed without much of the bolt-on silliness that takes these types of bikes away from their sporting roots. The Ducati is, after all, propelled by something very closely resembling a 996 motor. Why dilute that and weigh it down?

“For starters, both bikes are aimed at offering the rider stability without giving away too much of their ability to do the turn and burn on weekends once you pop the bags off.”

Similarly, when we first got the chance to test out Aprilia’s Futura a few weeks ago, we were impressed by how well the bike worked in all things sporty, making just enough concessions for comfort and the ability to put more miles behind you in a day than the motor has cubic centimeters. This motor, by the by, has ties to the company’s Mille, the same bike that goes up against the 996 in the World Superbike wars every weekend. Despite the seemingly parallel lines of the design philosophies inherent in each of these two bikes, the outcomes are very different when you get to know each bike’s intricacies.

Then again, why would you pop the bags off on either of these two bikes? They can both hold enough luggage for a string of overnight rides and are cavernous enough to contain most helmets. They also weigh very little and only minority effect each bike’s overall handling. Still, the bagged edge goes to the Aprilia for its integrated looks and slightly larger volume, while the Ducatis tend to be easier to pop on and off. Both systems feature the same (annoying) entry system that requires a key to either open or remove each bag. Maybe somebody in Italy needs to ring up somebody in Germany, as BMW still has the best working bags in the business, even if the bikes they’re affixed to fall behind these two when sport-touring leans more to the former than the latter.

Rolling along the highway, getting the chance to enjoy each bike’s virtues side-by-side, a funny thing happened. The Ducati’s motor felt more polished and noticeably smoother than the Aprilia, especially under acceleration. When droning along at constant throttle, the motors on both bikes felt very similar. There was only the familiar V-twin vibe coming through, and it was never unpleasant. The Ducati’s rider felt the vibes in the buttocks and foot pegs mostly, while the Futura pilot felt most pulses through the bars, with only a little bit seeping into the pegs. Again, very little vibes on either bike and to say one had more or less could only be discerned when ridden back-to-back, then back-to-back once more just to confirm things.

|

Under acceleration, however, it is a different story all together. Here, we got the first signs of just how lively the Ducati’s motor is and how smooth (read: flat) the Futura’s motor is. This is surprising when taking into account the fact that the RST manages to pump out 2.2 more horses and 6.1 more foot-pounds of torque at peak RPM than the Ducati, thanks to a displacement advantage of some 61 cubic centimeters. While making power, the Ducati goes about its business with a nice reminder of its racing roots. In direct comparison to the Futura, it’s quite lively, offering up a nice rush towards the upper end of the powerband, like a V-twin VFR800. Vibes are felt in the same places they popped up while just droning along, coming through only a bit more intensely, though never bothering us.

Conversely, the Futura’s motor feels rather bus-like. The 997 cc motor may pump out more power and move the bike along at a faster clip than the Ducati’s mill is able to manage (comparing claimed dry weights on both bikes shows only one extra pound residing with the Futura), but the way power is made is seamless and flat.

There’s never any surge or rush in power, and the motor tends to vibrate more than the Ducati’s when the throttles are whacked open. This is especially felt through the grips, and is most likely due to the larger displacement as well as the more rigid Aluminum frame. Its taller, squared-off front end keeps a rider’s entire body in still air, providing a cocoon for even our tallest testers who were creeping up on six and a half feet. So while the ST4 does a good job, the Aprilia manages to take things a step further. Also found on the styling exercise that is the Futura’s front end is the best headlight we’ve ever tested.

At night, climbing up out of the valley in Merced, heading into the hills of Yosemite National Park, Minime started the climb in the lead on the ST4. Within a handful of miles, he pulled over and swapped the Ducati for the Aprilia, noting that he was getting more light from the Futura that was behind him than from the ST4 he was actually riding. When daylight dawned the following morning, our first stint of the day was a twisty ribbon of asphalt heading up Highway 49, out of Mariposa (our previous night’s beverage and lodging stop) towards the town of Sonora. This first section of the day was about as clear, clean and tight as things would be all day. We knew this, and proceeded forward with throttles open more than these bikes are likely to see under “normal” operating conditions.

|

|

“Neither bike had problems in the twisties, though both would touch down their center-stands (which are a blessing on any bike with a chain that’s not destined only for race track use) when leaned way over in a manner these two bikes are highly unlikely to encounter in normal use.”

Source link