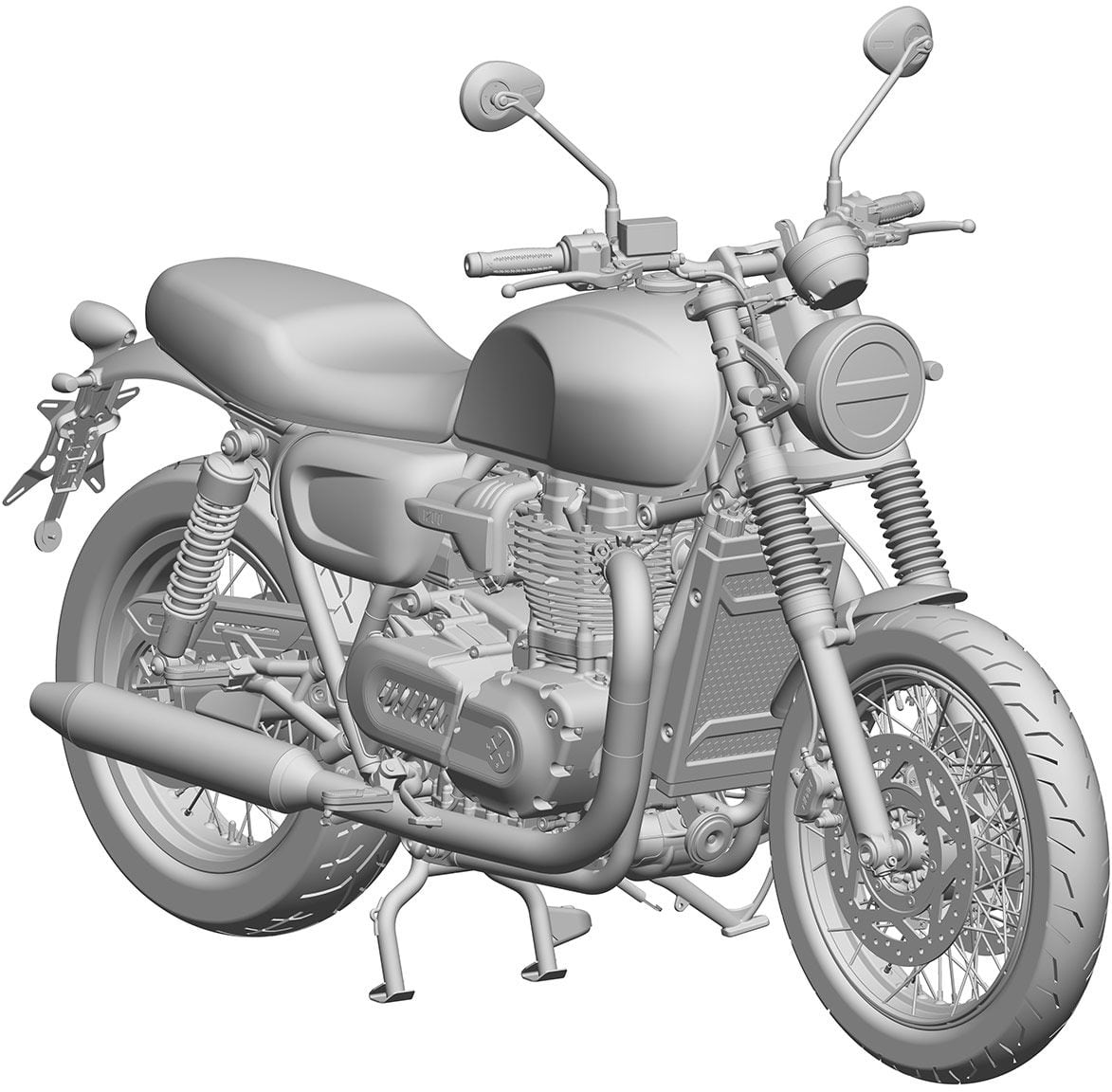

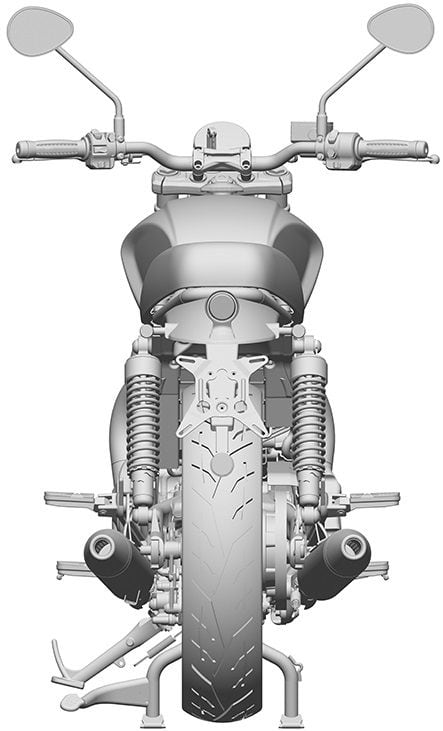

These renderings show Brixton’s design will likely have a 1,200cc displacement, with other elements also closely mimicking that of the current Triumph Bonneville. (Brixton/)

When it comes to capturing the style of the world-beating British parallel twins of the 1960s, Triumph’s Bonneville range is hard to beat—but upstart bike maker Brixton is out to grab a slice of that market with its upcoming retro twin. First shown as a concept back in 2019, with no confirmed production plans or even technical specifications, Brixton’s biggest bike yet has since been edging toward showrooms, and now the firm has filed design patents that show 3D renderings of the final production model. As well as revealing the changes that have been made since that original concept appeared, the designs also finally confirm certain key technical details including the all-important capacity.

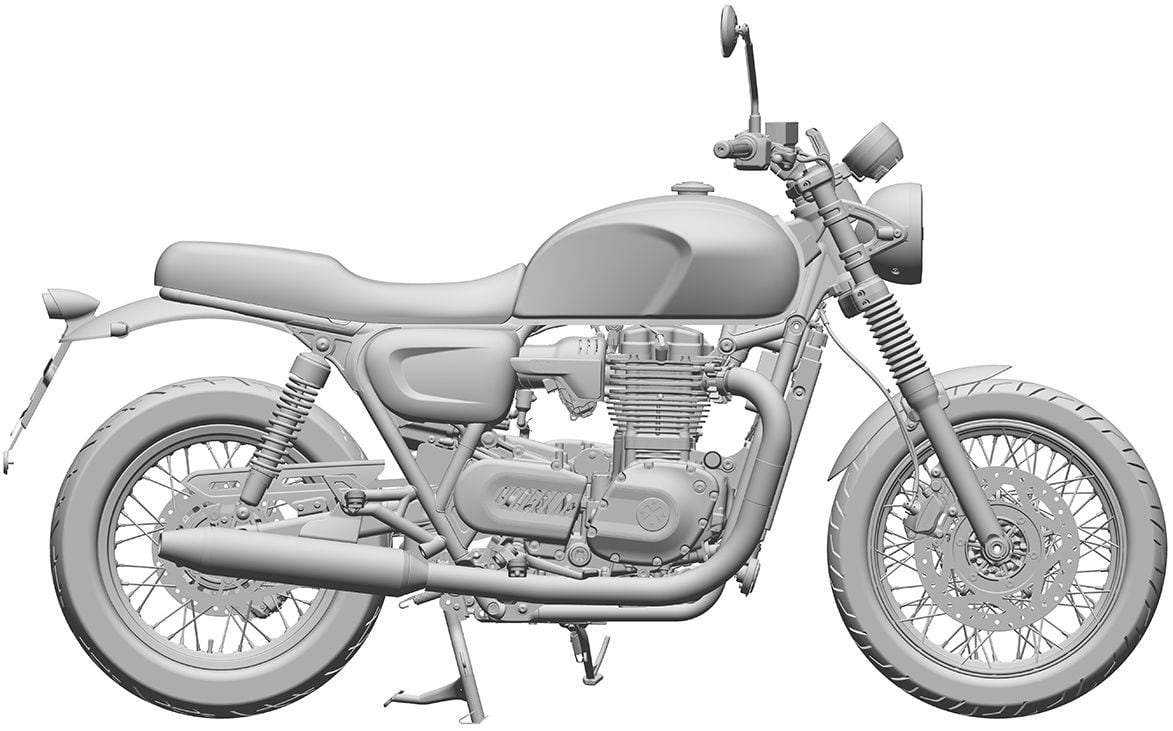

Drawings betray a liquid-cooled engine, also with a SOHC cylinder head and rocker-operated valves. (Brixton/)

While the bike has been talked up as being in the region of 1,200cc, matching Triumph’s larger Bonneville T120, that capacity hasn’t been confirmed until now. The new patents include details of the side panels, used to hide the modern fuel-injection system, with the “1200” badging clearly on view, removing any lingering doubts as to the Brixton’s size or the fact it’s aimed squarely at the Bonneville.

The Brixton concept wasn’t given a name, but the project is being developed under the code “M31,” so we’ll use that title. The M31′s design work has been done at Brixton’s base in Austria, where the firm’s parent company—the KSR Group—is based. However, the bikes are developed and manufactured in China by Gaokin, and while the “Brixton” name is shared with a district in London it’s not a brand with British connections or heritage. While that clearly presents a hurdle when it comes to competing with a company that has the heritage and recognition that Triumph enjoys, it’s worth pointing out that the current Bonneville models—like all of Triumph’s mass-made machines—are manufactured in Thailand. The current iteration of Triumph, revived in the 1990s by house building magnate John Bloor, is also a different entity to the original brand, which folded in 1983.

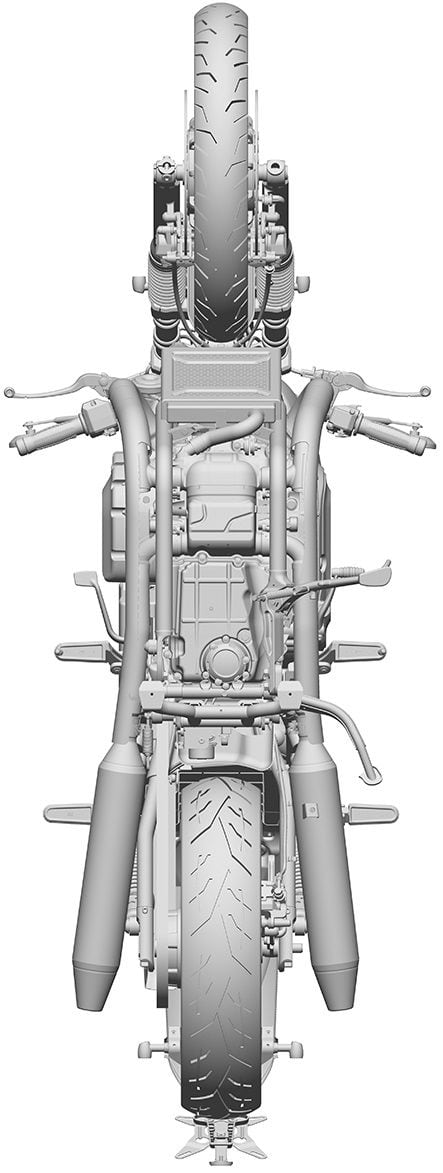

Double-cradle chassis design is likewise similar, with the same general layout as the standard Bonneville. (Brixton/)

Looking at the new patent images of the Brixton, it’s clear the firm has used the current Bonneville as a template. The frame design is extremely similar, though since it’s a fairly normal, tubular steel, double-cradle chassis there isn’t a huge scope to be different.

Like the latest Bonneville, a vertically mounted radiator behind the front wheel betrays the fact it’s liquid-cooled despite the engine’s extensive cooling fins. The engine’s similarities to the Bonneville’s don’t stop there; it also appears to have the same general layout, with an SOHC cylinder head and rocker-operated valves, and while the actual castings of the cases, cylinders, and heads are unique to the Brixton, the two engines’ silhouettes are almost identical.

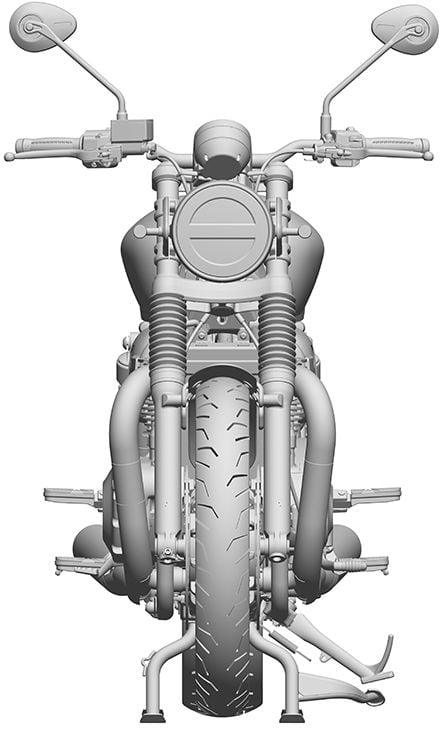

Seating, ergos, and tank design tick all the familiar retro bike boxes; key in the ignition switch suggests the M31 won’t be keyless. (Brixton/)

With the same layout, capacity, and construction, it’s safe to assume the performance level of the Brixton M31 will be close to that of the Bonneville, which means it’s likely to make around 80 hp—a fairly modest target, as in some guises, like the Thruxton TFC, Triumph’s 1200 twin has been able to produce as much as 105 hp.

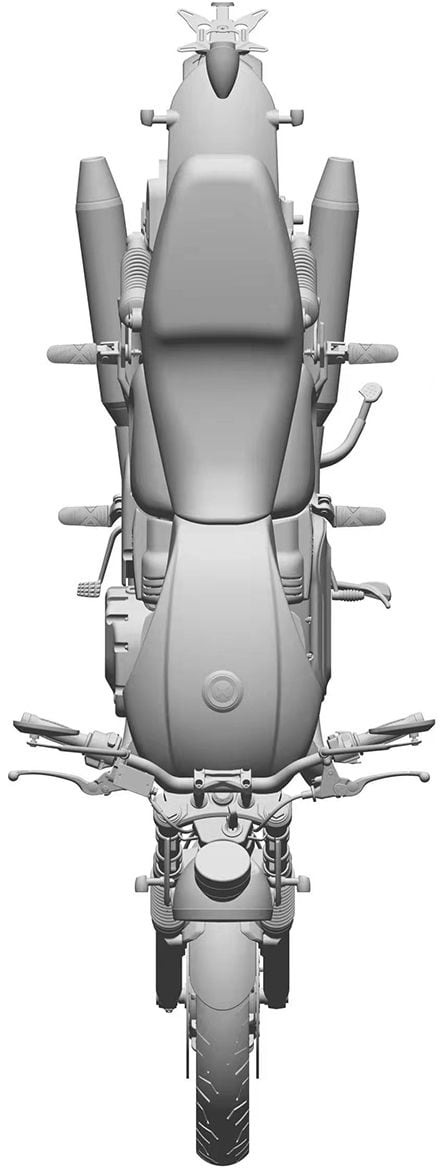

From underneath, you can see Brixton has likewise used Triumph’s solution of routing the true exhaust to a collector box (with a catalytic converter) under the engine. (Brixton/)

A view of the underside of the bike shows another area where Brixton has mimicked Triumph: the exhaust system. With the Bonneville, Triumph cleverly gives the impression of a traditional 2-into-2 exhaust, with each cylinder’s header running straight into the tailpipe, but actually there’s some visual trickery going on. A section of each visible, outer pipe is actually a dummy, and the genuine exhausts are routed into a shared collector box under the engine where a catalytic converter lurks. Brixton has borrowed the same solution, and the cat itself appears to be virtually identical to the Triumph unit.

Brixton’s design bolts the pillion footrest hangers onto the frame rather than welding them on, suggesting the same frame could be used in multiple iterations. (Brixton/)

While some of the bike’s design elements are inspired from existing models and the style ticks all the retro, 1960s Brit-bike boxes, the Brixton M31 patents also show the firm is at pains to avoid using off-the-shelf parts that might cheapen the overall image.

The brand’s compass-inspired logo appears everywhere, from the engine covers to the bar grips and footpeg rubbers, and even the key—visible in the ignition switch (and showing that the M31 isn’t using a keyless system)—is out of the ordinary, with a flick-knife-style design. The patent also suggests that Brixton is wisely designing the bike with multiple versions in mind. For instance, where the Bonneville’s pillion footrest hangers are welded onto the frame, the Brixton’s are bolted on, so the same frame could easily be adapted into a single-seat café racer or perhaps even a scrambler or touring-oriented machine.

Given the final appearance of the patents and the fact it’s been nearly two years since Brixton’s original concept bike was revealed, it’s likely the final version of the 1200 will be officially unveiled at a show later this year, with production following in 2022.