Most of the customs we drool over on these pages have little or no history. They’re usually modified after a few mundane years of weekend riding—or transported straight from the showroom floor to the workshop, in the back of a van.

Occasionally, though, we happen across a machine with a decades-long backstory. Like this street legal Harley XR750 tracker from Quebec, Canada, which houses a tuned Sportster engine in an XR750 frame.

Builder Costa Mouzouris originally created the street tracker over 25 years ago. “I built it for a customer in 1995,” he says. “I lost track of it, and then found it in a classified ad about 20 years later, still in original condition. I bought it back, and refreshed it this year with new paint and cast wheels.”

Costa had every reason to keep an eye out for this Harley, because it had history even before he rebuilt it: “The frame is a genuine 1972 XR750 item,” he says. “It was raced in the mid 70s to early 80s by a French Canadian rider.”

By the time Costa got his hands on it, the frame was damaged—probably after several crashes. And even worse, the steering neck was no longer in line with the rest of the tubing. So Costa had to cut off part of the top tube and the front down tubes. New chrome-moly tubing and a steering neck were TIG welded in place, and arranged so that a slightly taller Evo engine would fit the frame.

The engine also came from a crash victim: this time, a 1986 Sportster XLH883.

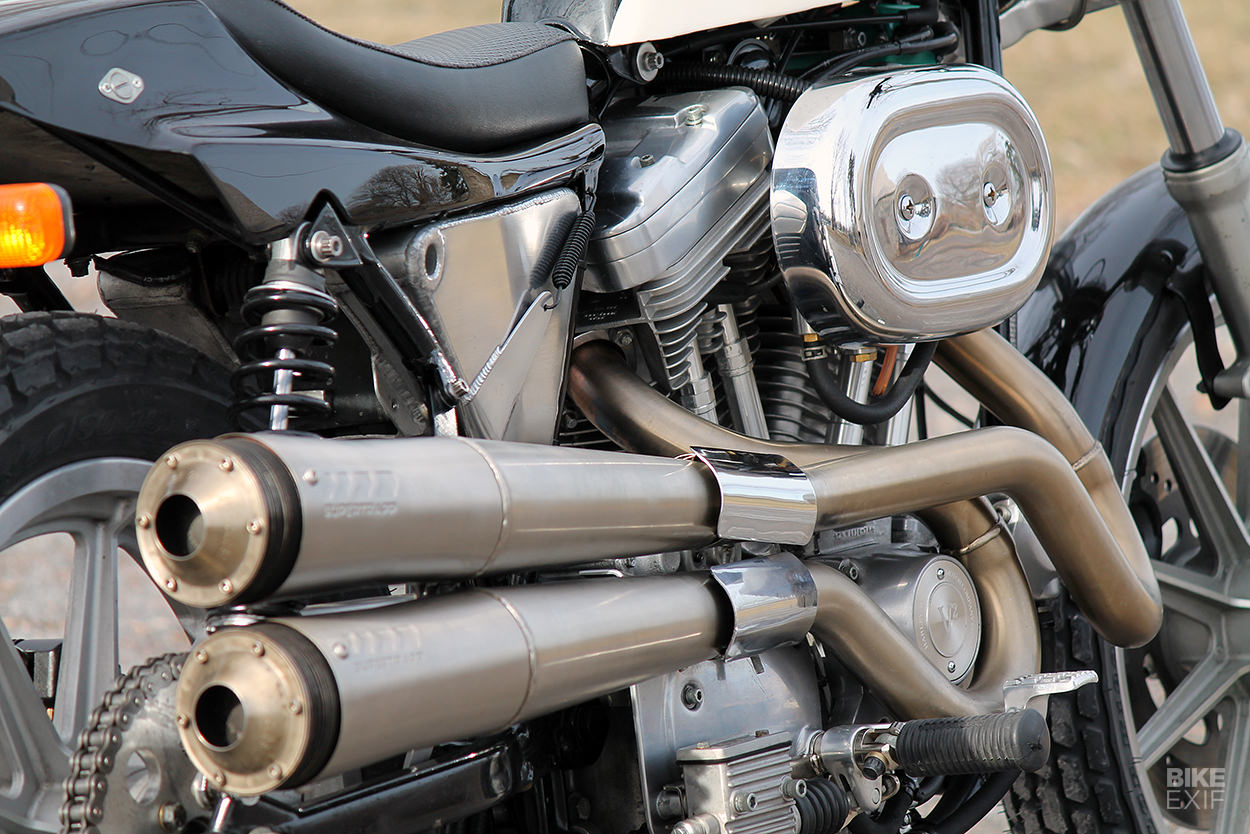

Costa bored the V-twin out to 1,200 cc, and fitted Harley pistons. The cylinder heads were modified for twin spark plugs, and a Dyna single-fire ignition and Andrews V2 Sportster cams (with more duration and lift) were installed. The carburetor is the famed S&S Super G.

“The goal was to have good power, but in a reliable package,” says Costa. “The crank was balanced, and the engine runs remarkably smooth for a rigid-mount four speed.”

The XR750 was originally built with a handmade high-mounted two-into-one exhaust, but the previous owner swapped it out for the SuperTrapp now on the bike. Unfortunately the original exhaust has been lost.

It wasn’t all plain sailing on the mechanical side, though. Costa had to modify the left-hand crankcase, because the nub where the alternator wire exits interfered with the XR frame swingarm pivot.

The oil tank is handmade from T-6061 aluminum plate, made to mimic the XR750 oil tank, but also now houses the battery.

For the rest, Costa wanted to keep things simple, especially when replacing parts. The electrics, brakes and front end are all standard Harley fitments but the shocks are Konis, which are more period correct than most modern units.

The gas tank is from a Sportster, but the eagle-eyed will notice that it’s shallower than stock and has been shortened by an inch at the front. The new tailpiece was a much simpler operation—it’s an aftermarket item designed for the XR750.

One of the first mods Costa made when the bike returned was the rims. “I installed the tubeless cast aluminum Harley wheels,” he says. “The front is a 19-inch, and the rear is an 18—from a late-1970s Sportster. I’m not sure I like the cast wheels, but I still have the original spoke wheels and will probably alternate between the two.”

We often wonder what becomes of the bikes we’ve featured. Some of them pop up on social media years down the track; others disappear without trace. We have a feeling there’s another half century of life left in this one.

Costa Mouzouris Instagram

Source link