“At 20, I was already too old to be a racer. I wasn’t that talented anyway, but I thought, ‘I can be a mechanic.’ ” (Jeff Allen/)

If you’re into AMA Flat Track or Harley-Davidson performance, the name Steve Storz is surely familiar. The self-taught tuner, fabricator, and engineer has been involved in flat-track racing for nearly 50 years, and has developed Storz Performance products since 1980. And the Ventura, California, business continues today, with exclusive development and production of Ceriani suspension parts.

The road—or rather racetrack—to Storz’s success was more organic than calculated. After graduating high school in 1968, the Nebraska native, then living in California, completed two years of college before enrolling in a motorcycle mechanics’ school and then landing a service job at Triumph of Burbank. But this wasn’t just any shop; it was owned by Jack Hateley, the racebike builder, sponsor, and father of AMA racer John Hateley. “I was just a wide-eyed apprentice when guys like Eddie Mulder and Gene Romero would come into the shop,” Storz recalls.

AMA flat-tracker Steve Morehead and H-D factory tuner Steve Storz, happy guys after winning the 1979 Syracuse Mile National and setting a new track record. (Courtesy Steve Storz /)

Before long, Storz attended his first flat-track race. “They said, ‘You ought to go to Ascot and see this,’” he says. “I could not believe what I was seeing—it blew my mind.”

RELATED: As the US Market Exploded, Japan Took Over

Although a capable rider, Storz knew his destiny lay in perfecting machines, not feet-up slides on the blue groove. “At 20, I was already too old to be a racer,” he notes. “I wasn’t that talented anyway, but I thought, ‘I can be a mechanic.’” He began to work on racebikes, gaining knowledge steadily.

The first Storz Performance shop in Ventura, California, in 1981. Here Storz developed a 42mm Ceriani fork for Sportsters, and Superbike Bar Mounts for Ninja 600s, early successful street products. (Courtesy Steve Storz/)

Storz absorbed everything and was astute to recognize that when certain doors open, you’d better walk through them. Starting in 1972, he did so, wrenching for AMA flat-tracker Terry Dorsch, and later joining Norton-Triumph and then Kawasaki as a product tester. “This was a good-paying job but uninteresting compared to racing,” he says. In 1976, Storz traveled east for flat-track tuner Shell Thuet and rider Hank Scott. “In Delaware, (Harley-Davidson racing manager) Dick O’Brien said, ‘We have an opening in the race department; you better get there.’ I flew to Milwaukee and worked with Bill Werner for three days, but no one offered me a job. So, Bill finally said to Dick, ‘Well, are you going to hire him?’ That’s how it started.”

With that, Storz became an official Harley-Davidson racing mechanic, initially with the company’s motocross program for rider Rex Staten. Then came a dream assignment; in 1977, flat-tracker Ted Boody and Storz led the AMA Grand National Championship in points before finishing second to Jay Springsteen—an incredible experience for the 26-year-old tuner.

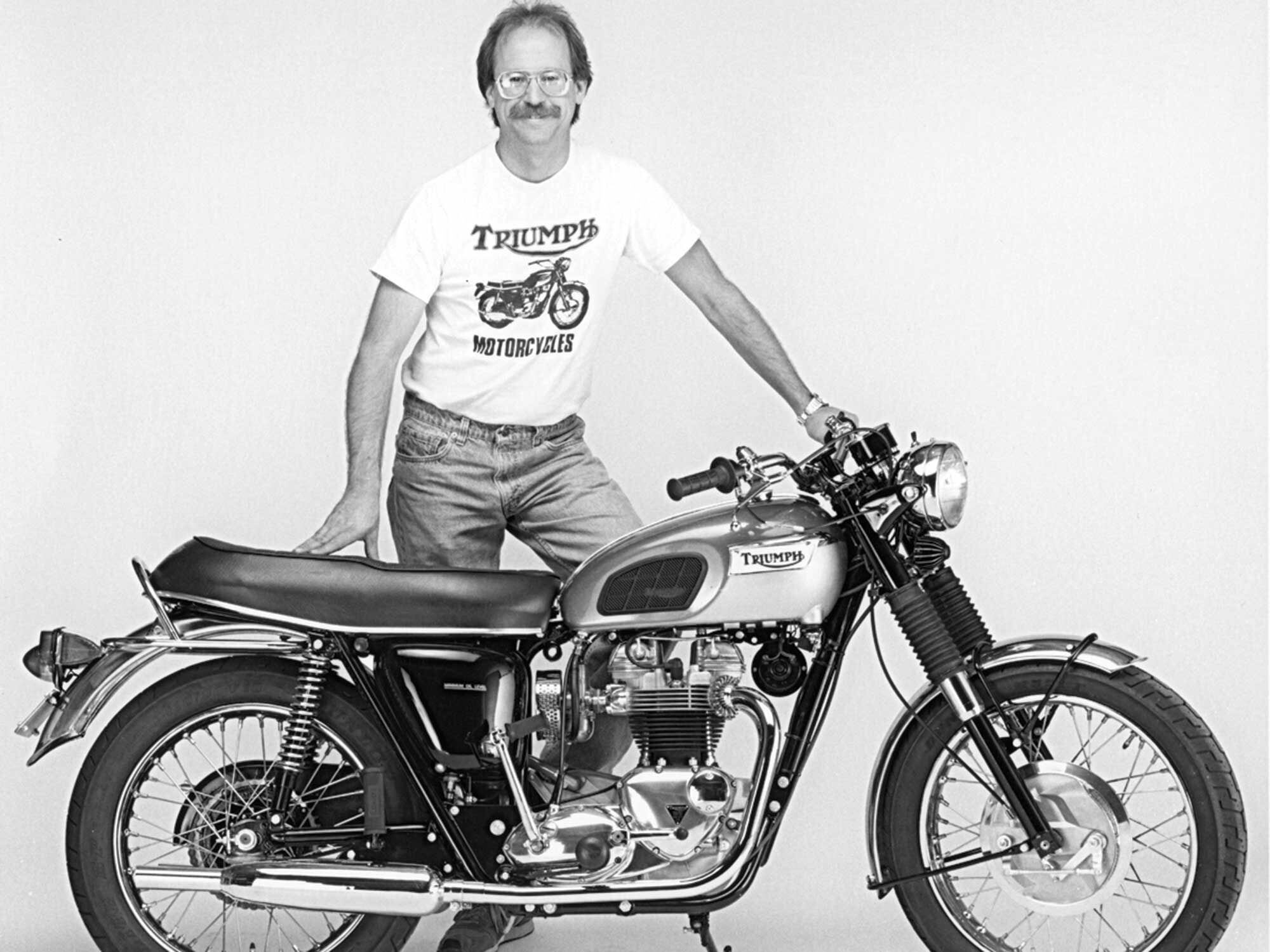

Storz with his restored 1970 Triumph TR6C, a duplicate of his first motorcycle that he enjoys occasionally riding today. (Courtesy Steve Storz/)

However, Milwaukee weather is not like Southern California’s, and after several years, Storz had enough bleak winters and summer heat, and headed west again, opening Storz Performance near Los Angeles to work on customer XR-750s and assemble his first product catalog, focusing on flat-track specialty items.

By the early 1980s, flat-track bikes were making more power and tires were improving, stressing the ubiquitous 35mm Ceriani forks. After getting to know an Italian who had worked for Ceriani, in 1985, Storz chanced a trip to Italy to see the factory. There he met Enrico Ceriani and miraculously returned home with an agreement for the company to produce a 42mm dirt-track racing fork to his specifications. In 1998, permission to use the Ceriani trademark in America followed.

The 1975 Norton-Triumph Racing Team. From left to right: Bob Tryon, Brent Thompson, Steve Storz, Jim Messler, and Sterling Goin. (Courtesy Steve Storz/)

Over the decades, Storz continued to develop and add products to his catalog, including street components, which are now the majority of the business. Another early result of his market savvy and product-development skills targeted the original Kawasaki Ninja, whose racy clip-on bars worked well on the track but were a pain on the street. Storz’s Superbike Bar Mount allowed using a normal tubular handlebar, expanding the bike’s usability.

RELATED: Jerry Branch And The Harley-Davidson Midget

Even after years of parts development, Storz still takes pleasure in conceiving, designing, and prototyping new components. An adept fabricator, he particularly likes working with aluminum. “It’s easy to machine, and anodizing gives it a good service life,” he says.

One highly recognizable complete bike Storz developed is the SP1200RR, a Sportster-based special that looks like the union of an XR-750 flat-tracker and a roadracer.

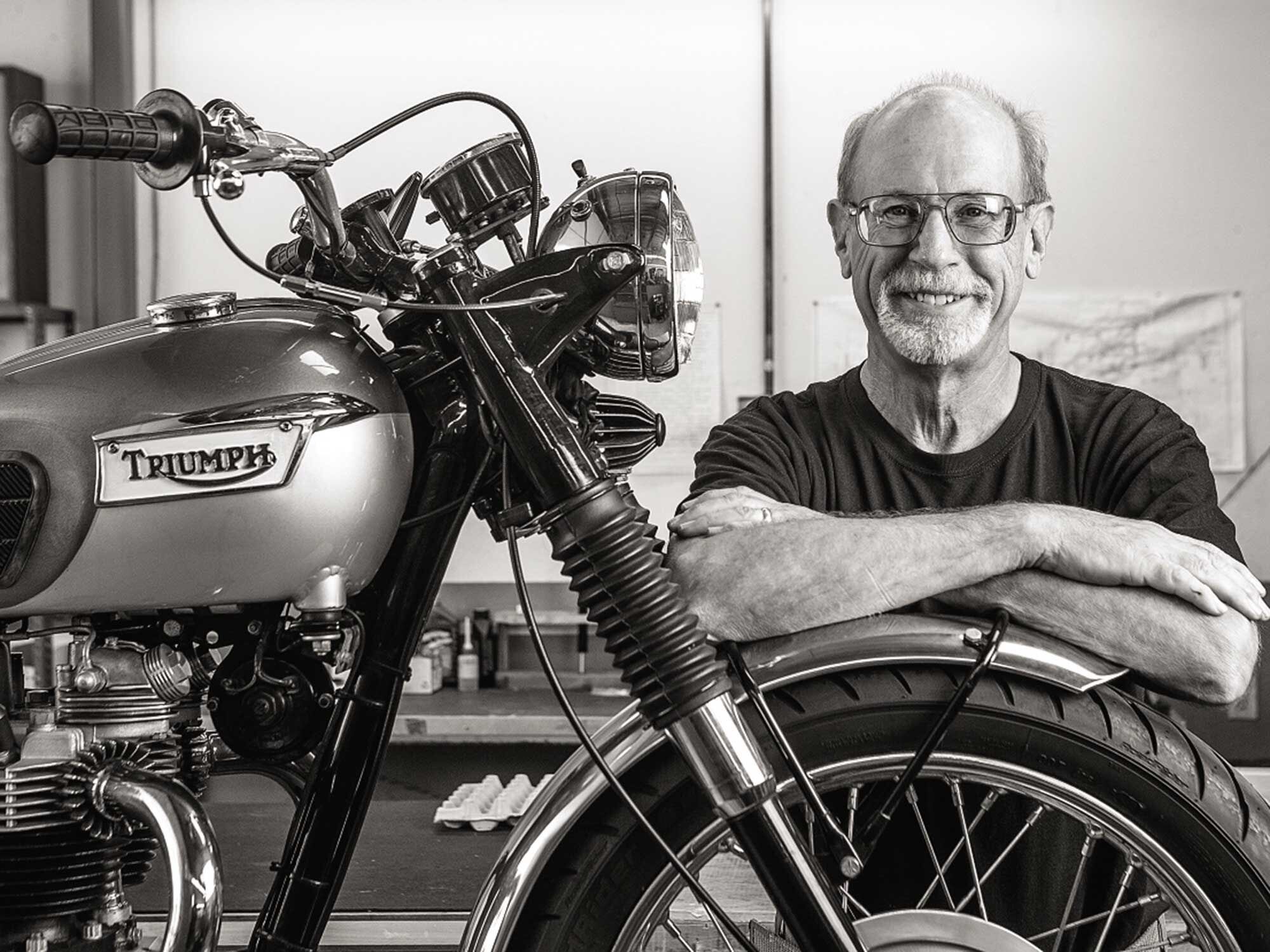

Steve Storz at his Ventura shop. (Jeff Allen/)

Today Steve Storz can be found at his Ventura shop, fulfilling orders—typically suspension, bodywork, and controls—or prototyping, his favorite part of the business. And with grown kids, his home and shop building paid off, and a Husqvarna Supermoto, trials bike, and vintage Triumph TR6 to ride, he’s a happy guy.

“I have been fortunate to work with some incredibly talented people,” he reflects. “From Shell Thuet to C.R. Axtell to Dick O’Brien, those people never gave up; they were not quitters in any sense of the word. I observed that dedication, and together with learning social skills, was very lucky to have it work out. The industry gave me a lot.”

This modesty is so perfectly Steve Storz. In appreciating what the industry has given him, he never mentioned what he has given it. Motorcycling needs more like him.

Source link

.jpg?itok=sC_7PkVU)